In the following featured legal analysis, AIW looks at the litigation work carried out thus far in Azerbaijan on devices infected by Pegasus. Specifically, this legal analysis looks at how Pegasus spyware was deployed to monitor journalists, lawyers, and activists in Azerbaijan and the legal steps taken within the existing national legislative framework to mitigate the unlawfulness of the use of Pegasus against these groups and individuals.

Background

Over the last few years, global-scale investigations carried out by international human rights organizations, investigative journalists, and/or whistleblowers have shown that the scale of the unlawful surveillance of individuals’ private lives through murky technology software has been pervasive, and widespread. Those findings also revealed the vulnerability of individuals’ fundamental rights and freedoms to private technology companies and the states deploying that technology for their personal interests.

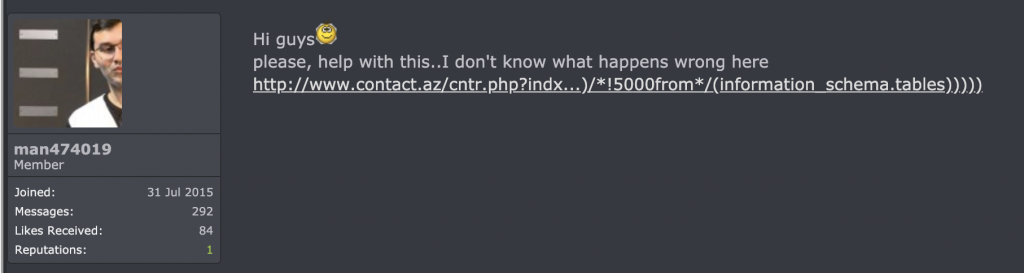

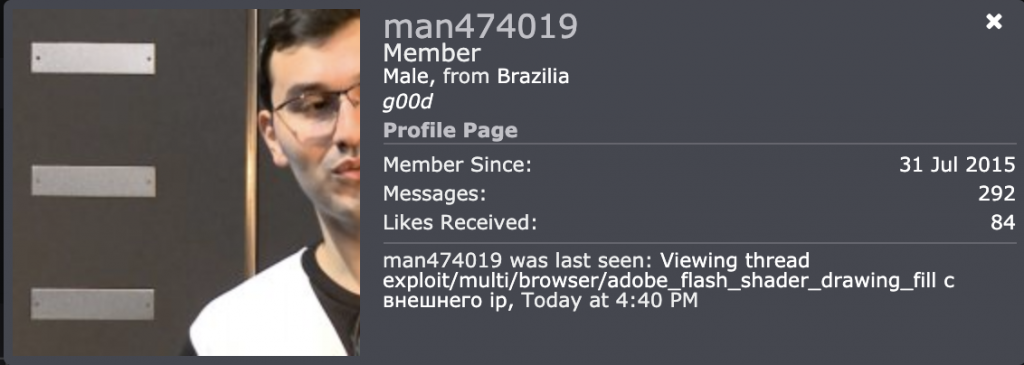

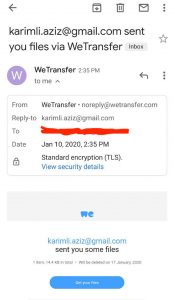

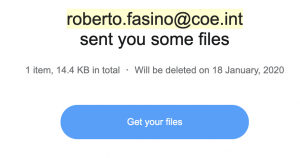

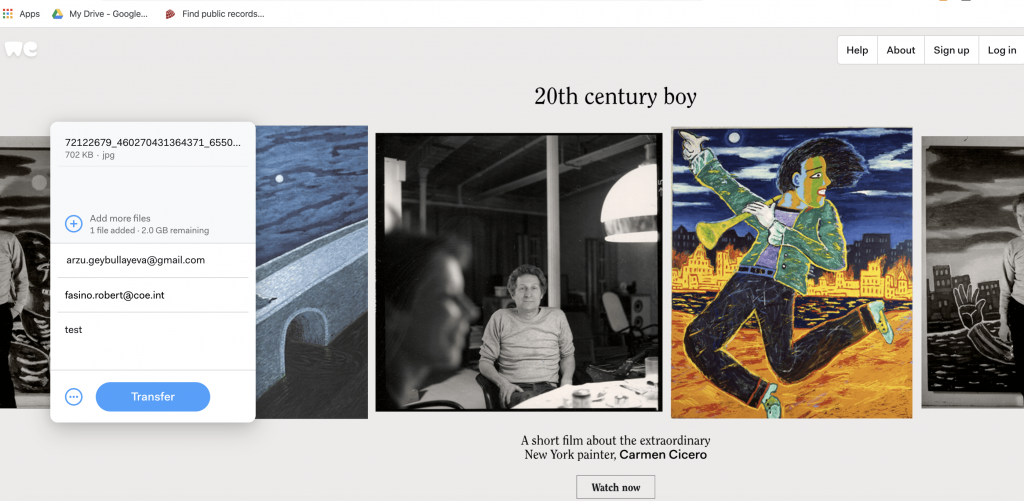

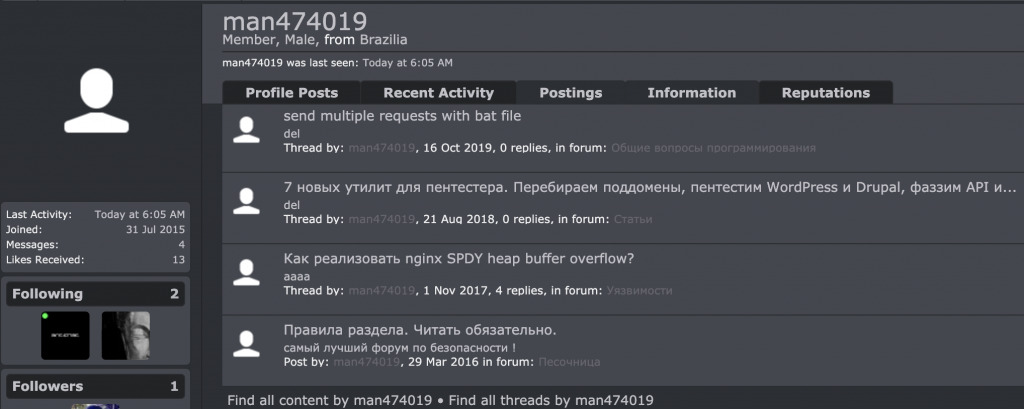

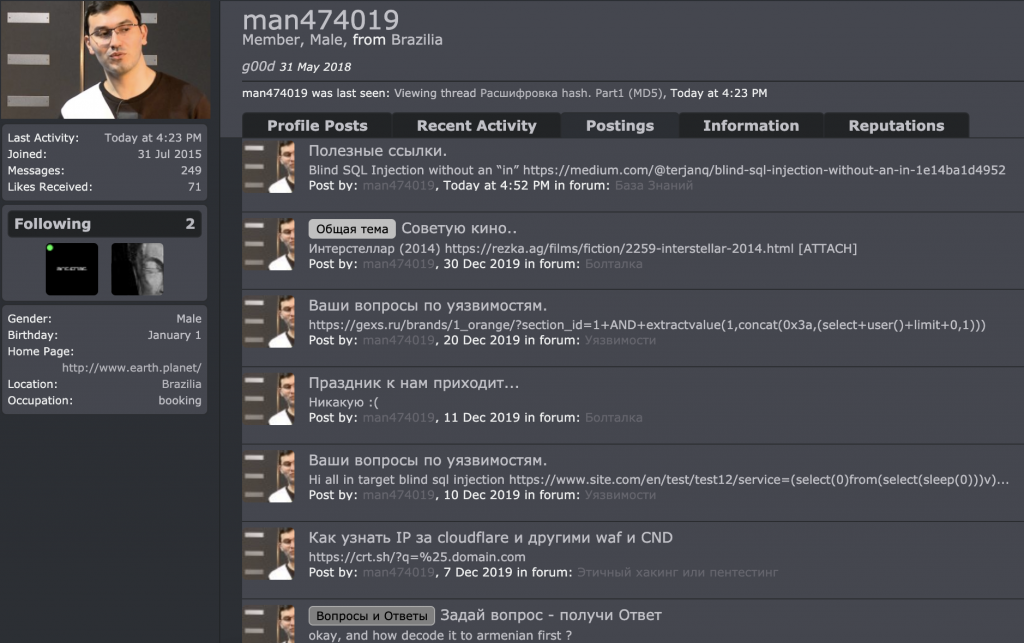

This has certainly been the case in Azerbaijan, where platforms like Azerbaijan Internet Watch (AIW) and others, have documented government-sponsored surveillance and cyber espionage activities. Especially vulnerable are the social and political activists. Several human rights monitoring organizations note the increase in cyber attacks on these groups in recent years.

***

Since 2011, Freedom House analyzes the state of Internet freedom in Azerbaijan in its annual Freedom on the Net report. Until now, each report indicated continuing deterioration of internet freedoms in the country.

Increased interventions on the internet freedoms often constitute a violation of fundamental rights and freedoms stipulated in national and international human rights documents, as such making states obligated to provide effective legal protection and recovery mechanisms against such violations.

However, as documentation and reports from recent years indicate, Azerbaijan thus far, failed to provide effective legal guarantees in cases of privacy violations through cyber-attacks, illegal collection of personal data, wiretapping, and account compromise. Despite routine calls made to the Azerbaijani authorities to investigate and bring perpetrators of cyber-attacks to account, no steps have been taken.

As a result, Azerbaijan continues to systematically fail in providing effective legal remedies and sound investigations against state-sponsored digital attacks and surveillance. Moreover, despite evidence-based reports of targeted and coordinated cyber attacks against activists, the government thus far has not investigated and/or provided effective legal guarantees.

***

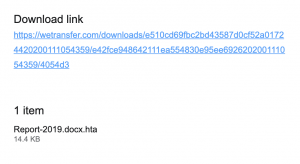

In July 2021, an international collaborative reporting initiative #PegasusProject documented how NSO Group, an Israeli surveillance company, sold Pegasus, a hacking software, to authoritarian regimes to target human rights activists, journalists, politicians, and lawyers among others worldwide. The investigation and the list were coordinated and obtained by the Paris-based journalism nonprofit Forbidden Stories and advised by Amnesty International Security Lab.

The investigation determined that Azerbaijan was among the top 10 countries deploying Pegasus spyware.

Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), which was one of the partners in the global investigation, discovered that out of the 50,000 phone numbers that were leaked, 1000 were from Azerbaijan. OCCRP was able to identify 245 numbers and as a result, concluded that a fifth of these numbers belonged to journalists, lawyers, human rights and political activists, politicians, and their family members. OCCRP published a list of identified civil society activists whose devices were confirmed to have traces of Pegasus spyware.

***

Following the Pegasus Project leak, on July 22, 2021, on the National Press Day in Azerbaijan, journalists and human rights defenders gathered in a virtual round table discussion titled “New digital threats to critical voices” initiated by the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety. The group discussed the importance of protection mechanisms against such mass surveillance and stressed the need to join efforts and seek legal remedy through domestic and international courts. As such, an operative group of lawyers was assembled to develop applications and appeals to domestic authorities and the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

Since that meeting and at the time of writing this report a total of four groups were formed, led by different lawyers, representing in total of 62 applicants. It is worth noting that some victims hesitated to join these collective complaint groups due to safety concerns.

Complaints and lawsuits were lodged as early as August 2021. Lawyers and advocates representing all four groups, prepared complaints to the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Republic of Azerbaijan, claiming that their clients’ mobile devices were illegally infected by Pegasus spyware leading to violations of privacy, freedom of expression guaranteed under the national laws and European Convention on Human Rights, the right to effective remedies and the right not to be subjected to restrictions of Convention rights with improper motives or ulterior purposes (Article 18).

Applicants in the group of cases led by advocates and practicing lawyers requested the Prosecutor General’s Office to open a criminal investigation based on the evidence revealed as a result of the global investigation. Specifically, the lawyers noted that several articles of Azerbaijan’s Criminal Code – Article 156, “Violation of privacy”, 271, illegal access to a computer system, 272, illegal interception of computer data, and 302, “Violation of the legislation on operation-search activities”, were violated as a result of the committed criminal act.

According to Article 156 of the Criminal Code (“Violation of privacy”), actions that violate privacy are prohibited and are the basis for criminal liability. According to Article 156.1 of the Criminal Code, the distribution, sale, or giving to someone else, the illegal collection of information that is a secret of personal and family life, documents reflecting such information, video and photo recording materials, sound recordings, causes criminal liability. Article 156.1 of the Criminal Code aims to protect the information that constitutes the secret of personal life and is derived from the goal of protecting people’s constitutional right to privacy. The object of this crime is people’s personal life information.

According to Articles 271 (illegal access to a computer system) and 272 (illegal seizure of computer data) of the Criminal Code acts of deliberately entering a computer system or any part of it without the right to access it, by violating the security measures, or capturing computer data stored on a device, or with other personal intent are criminalized.

Article 302 of the Criminal Code (“Violation of the legislation on operation-search activities”) criminalizes unlawful measures by the persons authorized to carry out operational-search activities in the absence of the grounds established by legislation.

In all of the legal complaints submitted based on the list of violations mentioned in the paragraph above, the team of lawyers asserted that the findings of the Pegasus investigation, put their clients at risk of both secret surveillance and of having their communications data unlawfully intercepted by the authorities or third parties who own the software. None of the identified civil society representatives targeted by the spyware were under lawful investigation. As such lawyers demanded that the Prosecutor General’s Office of Azerbaijan launch a criminal investigation, including the possible role of the Azerbaijani law enforcement in the mass surveillance activities. The legal representatives of all clients said, the state is obligated to provide effective legal guarantees against the abuse of spyware tools against citizens as the latter may constitute unlawful interferences to the right to private life, freedom of expression, and in the case of failure to fully and duly investigate, violation of the right to an effective remedy.

Due to the lack of legal remedies in cases of severe privacy violations, within the Azerbaijani legislation, advocates and lawyers relied on Article 8 (right to respect for private and family life), Article 13 (right to an effective remedy), and Article 18 (Limitation on use of restrictions on rights) of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Between July 2021- July 2022, one of the advocates representing one of the four groups of applicants, separately applied to the State Security Service [SSS], the Ministry of Internal Affairs [MIA], the Ministry of Digital Development and Transport [MDDT], as well as the Ombudsman office requesting an investigation, along with the Prosecutor General’s Office. None of the advocate’s appeals were successful. None of the institutions investigated the complaints or provided reasonable answers.

Overall, the lack of effective response on behalf of the law enforcement authorities, against complaints requesting to open a criminal investigation, indicates there were and still are significant flaws and delays in the investigation process, despite the evidence collected through forensic methodology by the international organizations. Nearly a year later, the law enforcement authorities are yet to take formal investigative actions, despite the complaints containing forensic evidence obtained from the examined mobile devices.

Court litigations

In all of the legal cases, the lawyers provided circumstantial evidence (contextual information) for how Pegasus infected the mobile devices of applicants. Specifically, the lawyers shared detailed information about the purpose of the Pegasus spyware and the potential state agencies that might use it. Relying on the existing national legislation the lawyers also established the legal grounds for using surveillance programs to intercept private communication or other private data from technological devices, including mobile phones.

Advocates representing the four groups submitted complaints to the local courts against the general prosecutor’s office for failing to explain why it sent lawyers’ Pegasus-related complaints to the State Security Services in the absence of justifications or notice. It was the responsibility of the General Prosecutor’s Office to investigate lawyers’ complaints, but instead, it sent them directly to State Security Services. This was unlawful and baseless. Yet, despite the unlawfulness of the act, the local courts did not satisfy these complaints and returned them without consideration (issued decisions in a similar text that they were considered inadmissible).

This explicitly demonstrates that the law enforcement authorities and domestic courts of Azerbaijan refused to effectively investigate the complaints and failed to provide any legitimate grounds for refusing the investigation in the first place.

One of the four groups involved in litigation procedure, includes activists, human rights defenders, journalists, and other public figures, who were previously subjected to different legal harassment by the government. Advocates and lawyers representing this group are demanding that the Prosecutor General’s Office investigate the possible role of the law enforcement authorities on the grounds that the use of spyware tools breached the defendants’ rights guaranteed under both the Constitution of Azerbaijan and the international treaties Azerbaijan is a party to.

The complaint consists of the summary of the complaint itself, information about the applicant, and information on the use of Pegasus to track the defendants, including applicants’ claims and petitions based on the substantial and procedural grounds of the complaint.

In their fifteen-page complaint, the applicants referred to the findings of Pegasus investigations, alleging that their phones were tapped and infected with Pegasus. The complaint also stated that listening and monitoring of the complainant through the use of Pegasus violated Articles 32, “Right to inviolability of private life” and 47, “Freedom of thought and speech” of the Constitution of Azerbaijan, and Articles 8, 10 and 18 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) as the breach was politically motivated. Lawyers also claimed that the surveillance was in violation of Articles 18 and 19 of the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as the jurisdiction of the Human Rights Committee on the implementation of that Covenant.

In addition, 11 petitions were attached by the lawyers, to the submitted complaints, requesting certain actions from the Prosecutor General’s Office that was necessary for an impartial and comprehensive investigation. These petitions included:

- Obtaining testimonies of applicants;

- Submitting official requests to Amnesty International Forensics team and the OCCRP for forensic investigation of identified devices;

- requesting the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the State Security Service to obtain a list of persons who carried out the interception of the devices;

- obtaining information on the purchasing of the spyware from the “NSO Group” company;

- requesting information from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the State Security Service, and the State Special Protection Service of the Republic of Azerbaijan about any relevant instructions on preventing human rights violations during the use of the Pegasus or similar programs;

- obtaining information on whether the officials at the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the State Security Services, authorized to carry out an operation-search measure, were involved in training on legislation and human rights standards.

It was also noted that the applicants, were law-abiding citizens, engaged in public and political activities, and were not engaged in criminal activities. As such the targeting of these individuals with Pegasus, was politically motivated and criminal given the absence of any mandatory, investigative, or judicial acts, within the scope of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CPrC) Article 177.3.5, and as a result, the use of Pegasus on their devices was in violation of targeted users’ rights and freedoms.

According to Article 443.1 of the CPrC, investigative actions over mobile phones and other communication devices are usually carried out on the basis of a judicial act. In the cases where these investigative actions are carried out without a court decision, on the basis of the investigator’s reasoned decision, after the completion of the corresponding investigative action, the investigator must inform the court conducting the judicial control and the prosecutor conducting the procedural management of the preliminary investigation within 24 hours and verify the legality of the investigative action carried out within 48 hours.

According to Article 215.1 of the CPrC, it is mandatory to conduct a preliminary investigation in all criminal cases, except for the investigation conducted in the form of simplified pre-trial proceedings for crimes that do not cause a great public danger.

Moreover, when responding to the lawyers’ complaints, the Prosecutor General’s Office, determined that the applicants’ complaints had to be sent to the Investigative Directorate of the SSS. Which is contrary to Article 215 of the CPrC and was contested by the lawyers who submitted a complaint to a local district court. The lawyers argued that it was illegal and unreasonable for the General Prosecutor’s Office to forward the complaint to the SSS for further investigation without any justification. At the same time, the transfer of the pre-trial investigation to the SSS, which is (potentially) a party of interest in the case, violates the procedural rights of the applicant on the personal life and freedom of expression, as well as the right to the effective remedy provided by Article 13 of the ECHR (taken together with Articles 8 and 10), because SSS will not be able to carry out the work related to the alleged illegal actions of its employees in accordance with the principle of objective impartiality. In addition, there are no normative legal grounds that could demonstrate the objective independence of the Investigative General Department of the SSS from other structural divisions of the Security Service.

Explainer: Lawyers reasoned that Pegasus was provided to the police and security agencies. From this point of view, based on the circumstances of the case, there are sufficient grounds to assume that the listening and online monitoring of the complainant was carried out by an employee (colleagues) of the police and (or) security agencies. In such a case, the prosecutor’s office cannot hand over the case of the preliminary investigation to the investigative body of the institution that carried out such hearing and monitoring. Otherwise, such an investigation would be subject to a conflict of interest in the case. In this regard, the elimination of conflict of interest in the investigation of a criminal case is one of the requirements of the criminal procedural legislation. Summarizing the above, it becomes clear: a) referral of the complaint to the State Criminal Court is a violation of the investigative responsibility defined in Article 215.2 of the Criminal Procedure Code; b) referral of the complaint to the DTC contradicts the principle of conflict of interests contained in Article 1.1 of the CPrC; c) referral of the complaint to the DTC is a violation of the human rights of potential victims (interested persons) defined by Article 1.4 of the CPrC, in this case, the right to request an effective procedural investigation; d) the referral of the complaint to the State Prosecutor’s Office is a contradictory decision and gives the impression that legal proceedings have been initiated to listen and monitor the complainant, as well as this referral was carried out by the wrong structural unit of the General Prosecutor’s Office.

Responses of law enforcement authorities

The General Prosecutor’s Office’s response to complaints was to forward the complaints to the State Security Service (SSS) for further investigation, without informing the applicants and without providing any explanation for the reasons for doing so.

The SSS, in all four groups of cases, refused to give an official written answer to the applicants about the investigation of their complaints (although they are required to do so by law). Officials from SSS informed lawyers verbally, that SSS did not monitor the applicants through Pegasus and therefore no written responses would be given.

As a result, advocates representing all four groups filed lawsuits against the General Prosecutor’s Office and the SSS for inaction and refusal to launch a criminal investigation.

It was not until August 2022, that the SSS started to summon a number of civil society members and journalists (applicants) to obtain their testimonies in regard to allegations of the tracking of their phones by the Pegasus software. Reflecting on the delayed response, one of the targeted civil society activists, and the chairperson of Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Center, Anar Mammadli, said this was simply a sign of lack of action.

In their responses to some of these complaints, the General Prosecutor’s Office and the Ministry of Internal Affairs said it was not possible to conduct an investigation on the complaint. Moreover, in relation to some of the applicants, in their response, the General Prosecutor’s Office, said, “the information on the features of capturing and tracking personal secret information was not determined by means of the Pegasus spy program,” but stopped short of explaining how then the information was obtained if it was not through Pegasus.

Since the engagement of advocates in pursuing these cases in domestic courts, the proceedings in all four groups are pending at different instances. Only 15 applicants were sent to the Strasbourg Court thus far. Advocates are currently seeking to exhaust domestic remedies to apply to the ECHR in the remaining cases.

Conclusion and next steps in taking the Pegasus cases to the European Court of Human Rights

In addition to the Constitution and other national laws of the Republic of Azerbaijan, the right to privacy is recognized as an international human right in numerous international treaties to which Azerbaijan is a party. As a signatory of the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Azerbaijan has binding obligations to protect rights to private life, including private communication and other private data, from infringements, including unlawful search-operation and surveillance activities of law enforcement authorities and any interference by third parties.

On September 20, 2009, Azerbaijan ratified the Council of Europe Convention of 1981 (Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data (ETS No. 108) for the protection of personal data which also falls within the scope of private life as protected by Article 8 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) making its application in Azerbaijan compulsory.

The ECHR reiterates that any interference can only be justified under Article 8, paragraph 2, if it is in accordance with the law, pursues one or more of the legitimate aims to which paragraph 2 of Article 8 refers, and is necessary in a democratic society in order to achieve any such aim (see Kennedy v. the UK, paragraph 130).

In the context of handling complaints related to Pegasus cases by Azerbaijan’s law enforcement agencies and courts, the lawyers demonstrated, that the applicants were subjected to interferences to their right to private life contrary to the adopted national and international human rights documents. The lawyers’ subsequent complaints were related to the law enforcement and judicial authorities’ refusal to investigate complaints about those interferences, including secret surveillance without providing any explanations and sound reasons.

In all four groups of Pegasus litigations, the secret surveillance of mobile devices had no basis in domestic law as none of the applicants were declared as suspects or accused persons in any criminal investigations.

The Strasbourg Court has delivered many rulings on the protection of privacy and personal data against government-sponsored surveillance or state responsibility to protect individuals from violence by third parties (Guide on Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Right to respect for private and family life, home, and correspondence. Updated on 31 August 2021. Para 107.) In order for surveillance to be in line with the Convention, certain legal safeguards should be provided both in legislation and practice, according to the case law of the ECHR.

Explainer: the law must be precise and clear as to the offences, activities and people subjected to surveillance, and must set out strict limits on its duration, as well as rules on the disclosure and destruction of surveillance data. Rigorous procedures should be in place to order the examination, use and storage of the data obtained, and those subjected to surveillance should be given a chance to exercise their right to an effective remedy. The bodies supervising the use of surveillance should be independent, and appointed by and accountable to parliament, rather than the executive.

At the moment, advocates and lawyers, are in the process of developing their clients’ applications to the ECHR alleging that the laws governing the matters of secret surveillance, as applied in practice, and also the refusal of the law enforcement authorities and courts to investigate allegations of surveillance, do not provide sufficient safeguards against arbitrary or abusive secret surveillance and/or accessing of private communications data. Lawyers also complained they had no effective remedy – domestically – in respect of those breaches which can be achieved through national legislation that strictly abides by the case law of the ECHR. The lawyers alleged that no effective remedy was available under Azerbaijani law and that SSS’s investigation could not be rendered effective since it is not an impartial and objective institution to review allegations of possible abuses and arbitrariness of its own officials. As regards the surveillance, a State could arguably be liable in respect of whatever system of surveillance without offering adequate and effective guarantees against abuse according to the well-established case law of ECHR.

According to Azerbaijan’s criminal law system, there are two judicial procedures that may be used by an individual wishing to complain about the acts of the investigative authorities:

- complaint to supervisory-review and

- judiciary (first and appeal court instances) under the CPrC.

However, as seen throughout the domestic litigation process in the course of the last year, the domestic courts stated clearly that the General Prosecutor’s Office forwarding the complaints to the SSS were not subject to judicial review, and the SSS’s lack of action was also not viewed as a sufficient ground to allow judiciary review. This makes it unacceptable that an individual cannot lodge such a complaint without having at least the concrete decision of the investigative authorities, which in fact, constitutes de-facto rejection to investigate the complaint containing allegation about a criminal act committed against him/her. In the absence of domestic remedies against potential surveillance measures under Azerbaijani law, an individual would hardly ever be able to have his/her right to effective remedies, respected and ensured.

Explainer: In this connection, the case law of the ECHR notes that ‘In the sphere of secret surveillance, where abuses are potentially easy and could have harmful consequences for a democratic society as a whole, it is in principle desirable to entrust supervisory control to a judge, judicial oversight offering the best guarantees of independence, impartiality and a proper procedure (Roman Zakharov v. Russia [GC], § 233; İrfan Güzel v. Turkey, § 96).’ The absence at the national level of a judicial review of the law enforcement authorities reactions (inaction or refusal to investigate without a decision) to the complaints of individuals containing alleged unlawful surveillance and other infringements of the right to privacy excludes the state’s obligation to strike a fair balance between the competing public and private interests.

Therefore, Article 8 of the ECHR likely be found as violated without the opportunity for judicial review of the inaction of law enforcement authorities constituting de-facto rejection to investigate the complaint containing allegations of violation of the privacy of individuals as they had not benefitted from the minimum degree of protection against abuses and arbitrariness. According to the case law of the ECHR, the absence of a judicial review of the overall covert surveillance system which was entrusted solely to the state body which was directly involved in requests for the use of special surveillance means amounted to a violation of Article 13 in the light of Article 8 owing to the lack of an effective remedy (see: Association for European Integration and Human Rights and Ekimdzhiev v. Bulgaria, 2007, §§ 98-103).

As such these litigations expose that surveillance software not only harms individuals unlawfully targeted but also raises the question of insufficient legal guarantees in place to protect generally all individuals against possible unlawful surveillance and other kinds of privacy violations.

Finally, these litigations highlight the insufficient legal guarantees both in national legislation and practice, by creating significant legal precedent at ECHR, and by publicly uncovering and highlighting the inadequate national legislation which potentially can lead to gross human rights violations. Therefore, there is a greater need to challenge both national laws and the practice of state authorities’ system of secret surveillance, as the current system constitutes potential risks for interference with the rights of all users of telecommunication services guaranteed by the Convention and national laws.

![mass phishing attack against Azerbaijan civil society [updated]](https://www.az-netwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/computer-security-or-safety-concept-laptop-PQ7RZZ5-533x400.jpg)